At SeattleCoach, when we say we equip leaders to be great executive coaches, it means that we help them to learn to think systemically. It’s like this: The word “executive” is less a synonym for “big shot” than it is reflective of a coachee who is “the leader or influencer of a system.”

In other words, when we coach a motivated executive, we’re also coaching the people around him or her—whether or not we ever get to personally meet those people (though things often get a significant boost when we do). Either way, it is axiomatic that when the executive coachee changes, those people around him or her cannot not change. This works in families and it works in groups and teams too.

At SeattleCoach we encourage our coaches to ask some key questions “from the balcony” about their coachees’ meta-agenda as well as the scores of daily and weekly agenda that matter to them “on the dance floor”:

1. What do you want to work on?

2. Why does it matter to you in your vision for your life?

3. What are the key strengths that you could or will bring to this?

4. What will the evidence be that we’re on target?

5. Who else is in your thinking as we work together?

Here’s how coaching played out with one of my favorite executives . . .

In my informational interview with Steve, it was clear that he had a vision for the coming decade of his life. He’d spent fifteen years becoming a subject matter expert (sme) and a thought leader. He was good. So good that the company for which he’d worked seven years was asking him to multiply his influence through a new team of six talented managers.

As the “Great Pause” of the Covid-19 pandemic moved through the economy, Steve’s organization was asking him to become the director of a new team that would respond to the needs of an increasingly virtual market.

It was a once-in-a-lifetime offer and Steve was excited. He’d moved through the stages of change quickly (“I could never . . . hmmm. I know someone who did something like this . . . maybe . . . I might like it . . . even be good at it . . . what would my first step be? I wonder if people would respond to my style . . . If this team really succeeded . . . “). He’d taken the job.

His leader had introduced Steve and the new initiative with enthusiastic sponsorship. And then he suggested some sessions with me as Steve added the identity of director to his reputation as a SME.

In our first few conversations, we explored everything from Steve’s strengths and his style to his vision for his life. We looked at how his new position synched with that stuff, and where he could sculpt and customize the job to reflect his own brand. We identified a few markers of success for his first one hundred days.

In our fifth session, I asked him to tell me about the two best teams he’d ever been a part of. He responded with stories that were full of humor and learning, accomplishment and gratitude. I heard about faithful leaders and generous teammates and arguments that didn’t damage friendships.

As we moved on, I asked him to tell me a little about how his new team was developing. He’d worked with his leader to confirm each member.

Steve explained that since everyone was new and the assignment was challenging, that in both his one-on-ones and in their team meetings, there was lots of energy and creativity and hope. He was thinking about how to “capture this moment” here at the start. He’d worked with two of them on a team before, two were veteran individual contributors and two were new to the organization. Two members worked on other continents. Each one respected Steve’s reputation and seemed excited about the chance to work together on a new team with a new challenge.

I kept weaving my five questions into our conversations—and Steve began to anticipate them. And the trust in our partnership deepened.

Steve and I worked solidly for ten sessions and then one day he asked if I could sit in on a team meeting. He wanted me to watch him in action and to meet the members of his team.

We refined our agreement a little and talked about what he wanted me to keep to myself (not much). I asked him about his best hopes for my joining them. He smiled a little shyly and said that he wanted me to help him have a conversation with these six talented managers about how they could become one of the best teams he’d ever been a part of.

When as coaches our work includes both a leader and his or her system, we ourselves become part of the system, thus changing it. What will you bring that becomes contagious in the best of ways?

From our earliest days growing up in a family system, you and I learned how our individual actions affected other people—and our families as a whole. We learned that when something happened to one member, everyone else got involved or felt the impact. We learned what was required to survive and get love. And we probably learned early how easy it was to look for culprits when things went sideways.

Now, as coaches, part of our work is to steadily review all of our favorite habits, biases and triggers. Now, as we find ways to use our own lives as our principal instruments, we have a chance to become less automatic, and more curious and chosen. We find the value in the big picture, in the functioning of the interlocking parts. It’s usually more generative than dissection. Maybe we blame less. Maybe we stay curious when clumsy language threatens to obscure kind hearts. Maybe we get better at spotting true yet infrequent threats.

If we’re successful, we develop “eyes to see and ears to hear.” And as trust grows, and along with it, everyone’s coachability, we keep watching for what and who is becoming contagious.

Edwin Friedman was a rabbi and family therapist who found ways to apply Family Systems Theory to organizational leadership. More about him in a minute.

Remember this from earlier in our work together?

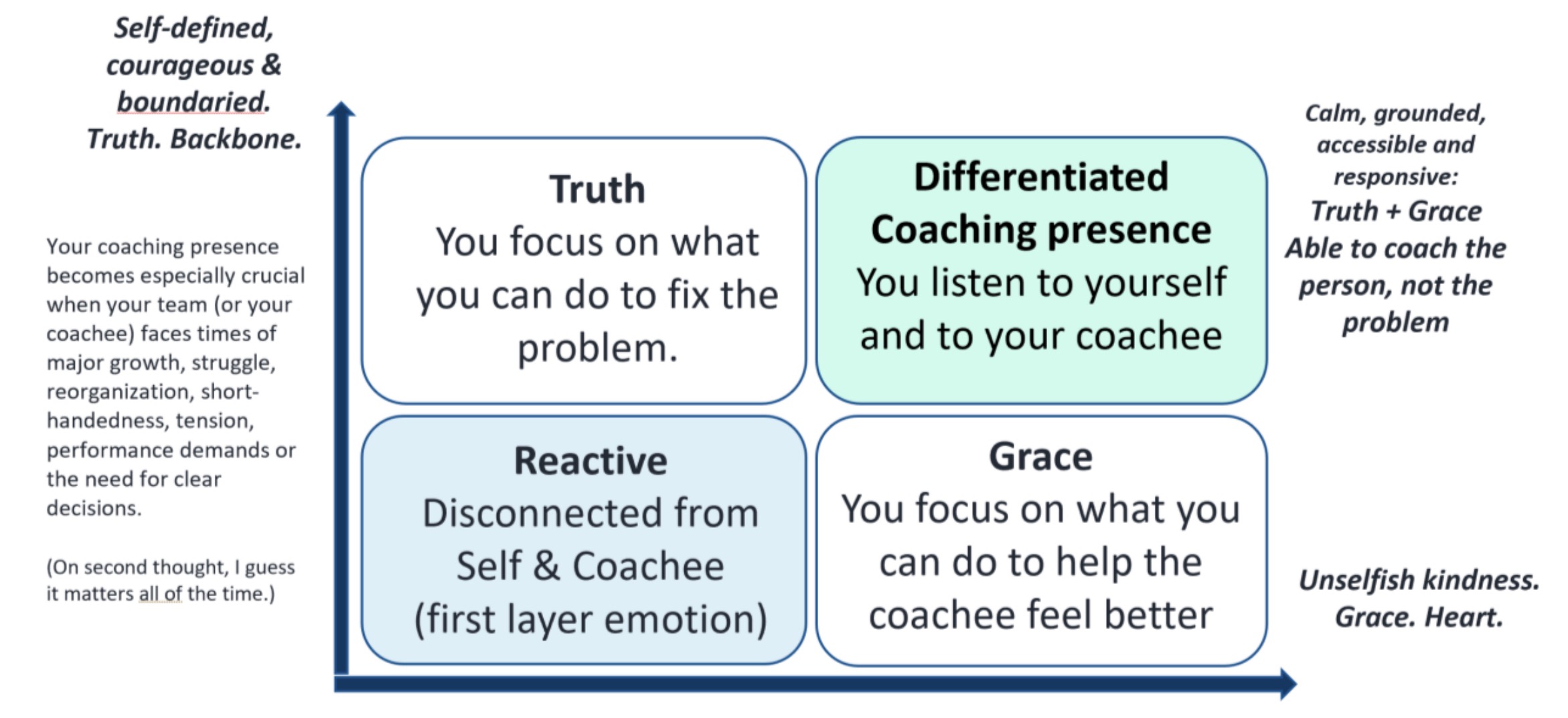

In Family Systems Theory, that upper right-hand corner is called “non-anxious presence” or “differentiation.” It’s the cornerstone of systemic intelligence. This is any leader’s most effective personal “home base”: You are calm and authoritative. You know how to listen to explore and how to listen to respond, balancing inquiry and advocacy. You know how to stand alone and you also know how to belong. Without self-preoccupation, you know how to listen to your own life. You know when to support and when to challenge. You can say what needs to be said (like the stuff everyone in the room already senses), without blaming. You coach the person more than the problem.

Family Systems Theory informs the best practices of coaches who become effective with groups and teams. Following are two core concepts to consider as you move between “on-ramp #1” to “on-ramp #2” as an executive coach.

1. Self-Differentiation

Friedman wrote, "In any situation, the person who can most accurately describe reality without laying blame will emerge as the leader, whether designated or not." I’ve seen the truth of this in team meetings when a new hire, rather than the positional leader became the person in the room who was most able to take a risk, to be vulnerable or persistent, or to take a stand while staying kind, open, clear and connected. Again, differentiated leaders know both how to stand alone and to belong, especially in necessary times of accountability, challenge, clarity, closure and disagreement.

As a self-differentiated coach, you know yourself. You have a reflective practice. You are non-anxious and more chosen than automatic in the way you respond. You know how to manage your own reactivity and are able to be present, vulnerable and connected with people. And as you join executive systems, you become almost automatically contagious as teams experiment with communicating—and even disagreeing—more freely.

Of course, a popular alternative to self-differentiation is trying to manage tough emotional stuff by reducing or totally cutting off contact with people who annoy us--or by creating triangles.

2. Triangles

An anxious system is characterized by emotional triangles, in which two conflicting members try to diffuse the anxiety between them by bringing in a third member. But this only serves to heighten the anxiety of the system. Maybe there is gossip. Or scapegoating. Or cutting-off.

During my days as a marriage and family therapist, exasperated parents would call asking if they could make an appointment for their surly teenager. “Maybe you can help (i.e. fix) her.” Invariably I would gently push back, assuring scared moms and dads that if they would participate, I’d promise to create a safe container for a different kind of conversation. My axiom from earlier in this article goes both ways: If a family changes, the individuals in it cannot not change.

Everyone creates triangles. On many teams, triangles are multiple and interlocking. There is always information about the system when it directs you as a coach to look at the person “whose fault all of this is” or at the person “who always calms us down.”

Coaches can help triangles to be the useful kind.

Following my initial meeting with Steve and his team, my focus has stayed mostly on Steve and his agenda. But we have enlarged our conversation to include the members of his team. They know me and I’m frequently with them, not daily or when they focus tactically or strategically on their deliverables, but in their team meetings and offsites when Steve invites them to focus on becoming the best team any of them has ever worked on.